Prehistory

Marton Cum Grafton would initially seem to be a typical quiet backwater village, where little has changed over the centuries.

This may be true when one considers only events that have taken place in and around the village. However due to Marton Cum Grafton’s unique location between a major river and the principle road to the north, combined with the proximity to towns such as York, Aldborough and Boroughbridge, Marton Cum Grafton has in fact been witness to some of the major contributory events that have shaped the social and political landscape of the North of England,

To properly understand the physical, social and political development of a village such as Marton Cum Grafton one must examine also the context in which this development took place, both in the whole of the British Isles and in the county of Yorkshire.

Firstly we must look at the landscape and the physical makeup of the area, an important factor in understanding the development of a settlement. This will lead to an understanding of the geological structure and history of the landscape on which it fits.

At the height of the last ice age, Marton cum Grafton lay beneath a large ice sheet, which filled the Vale of York, spreading out from the Yorkshire Dales and down from the Stainmore Gap (the A1/A66 junction) and lapping up against the margins of the North York Moors, which stood high above the ice surface. The thickness of ice was probably of the order of 100 to 200 metres and the terminus of the ice was to the south of York close to Escrick.

As well as having a grinding ice sheet above us, there would have been large rivers of meltwater flowing at the bed of the ice sheet that passed across the land that surrounds the two villages. These were responsible for depositing thick accumulations of sand and gravel, some of which can be traced today, along the route of the A168 to the south of Marton, and which is currently under excavation by the aggregate industry.

About 18,000 years ago, the ice sheet began to retreat northwards, thinning and melting over time. We don’t have a precise chronology for this retreat, but Marton cum Grafton was probably first exhumed from beneath the ice sheet around 15,000 years ago. We think that there are sediments in the base of Marton Carr that date from about 12,000 years ago.

During its retreat, the ice sheet paused at Marton cum Grafton, depositing a large accumulation of glacial debris (known as “boulder clay” or “till”), as well as sands and gravels laid down by meltwater rivers discharging from the ice margin. The steep slope that separates the two villages marks the stand-still location. At one time, and probably only for a short period of time, Marton was ice free but Grafton was still buried under ice.

Once the ice sheet had gone, warmer temperatures encouraged the spread of vegetation across the Vale of York and, up until about 5000 years or so ago, a dense woodland would have covered the landscape, probably made mostly of oak, elm, alder and hazel.

During this interval, known as the Mesolithic, scattered groups of hunters and gatherers would have lived and passed through the Vale, exploiting the rich woodland resources of plants and animals (the latter including abundant red deer). After about 5000 years ago, people began to develop agriculture and adopt a more sedentary life. They began to clear the woodland, to “manage” livestock and to grow crops.

A feature of particular note is the high numbers of springs that occur in the area. This is due to the high water table that occurs locally.

The location of natural springs is essential to understanding the location of settlements. Additionally, in prehistoric times, these springs appear to have come to mark divisions between tribal or family territories. These divisions were often marked by the placement of Barrows or other ritual structures and along spring lines. The location and purpose of such structures can therefore be inferred or explained by examination of the outcroppings of natural water supplies. This is an on-going area of investigation for this group.

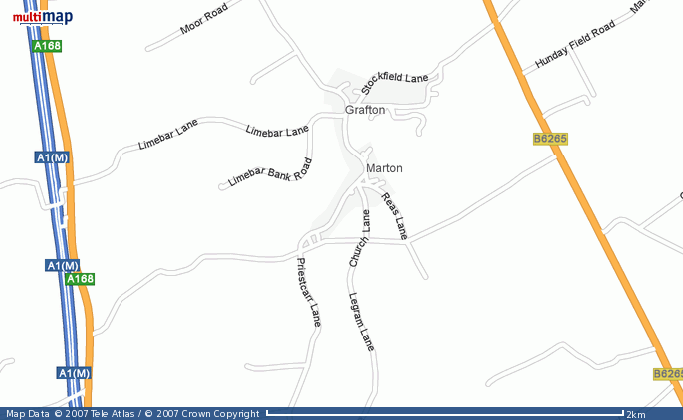

The map below shows the springs identified in and around the present village. These springs have been located either by examination of maps from the 18th century or by field survey.

From an archaeological perspective, the evidence for this Prehistoric activity is nationally scarce.

Only a few sites have been positively identified as being Mesolithic (Lit: Old Stone Age) in the UK, and even at these evidence is rare and scattered.

The typical evidence for this period is worked flints, of which none have been presented to the history group as yet.

Next (Neolithic)