Neolithic

Generally the Neolithic Age is taken to begin with the gradual trend for nomadic groups of Hunter Gatherers to begin a phase of urbanisation by settling in permanent village communities. In Yorkshire this is taken to have begun circa 4000BC.

The typical evidence we see from this period is increasingly sophisticated stone tools, usually in flint. Crude bone implements also survive, as do wooden objects when preserved in waterlogged conditions.

Pottery remains are rare. Habitation was in small (possibly family based) groups, with an evidently wider social grouping, covering large areas and incorporating many family groups. This is evidenced by the beginning of monumental earthwork monuments which began to be constructed around the country, especially in the South of England.

As the farming practices were crude, the yields were significantly lower, than we see today. As the climate warmed after the ice age, the benefits brought about by early farming, combined with the more temperate climate caused the population to expand and create greater competition for land.

This led to a series of migratory waves of early farmers, into less fertile areas of the country. The Vale of York around Marton Cum Grafton was one of these areas.

Neolithic evidence, as intimated above, is scarce. This is as true for Marton cum Grafton, as it is, for any other area of the country.

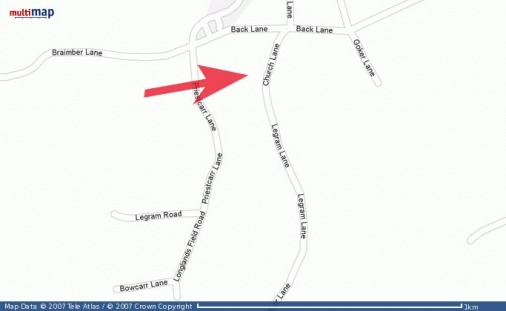

The only definitive evidence found and recorded to date is a Neolithic hoe discovered in 1927, and found in the fields to the South of the village, by a local farmer as shown below :

This discovery was reported in the Yorkshire Herald, at the time. Later in more detail, in a weekly supplement the paper records the find, as follows:

“The discovery was made by Mr G.H. Dewes, whose family has resided in the district since before 1660. The implement was found during the process of ploughing in a field of his adjoining the lane known as Priestcar, not far from the site of Marton Old Hall and the original village church. On being turned up, the find was declared to be a hoe of the Neolithic period. By the kindness of Mr. Dewes it was sent to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, in whose museum in Lendal, York it now reposes. Dr. Walter Collinge, the Curator of the museum, emphasised the great value and interest of the find, and the thanks which are due to the Vicar, the Rev. A.B.Browne, for his prompt action in the service of archaeology. The hoe is the only specimen of its kind possessed by the museum.”

It was estimated that the original stone was about 5 inches by 3 inches by 1 1/2 inches in a roughly triangular form, with one side tapered to a sharp edge. There is a large hole through the centre of the stone for the handle, which was bored out of the hard sandstone manually, as identified by the shape of the hole, with a pointed stick and water. The manual method of rotating the stick between the hands, as opposed to using a bow which gives a more uniform hole, identified the find as early Neolithic, approx. 4000 B.C. making it contemporary with the Devil’s Arrows near Boroughbridge, and the greater Ure/Swale valley collection of monumental earthworks, the meaning and function of which are still being debated. See the Timewatch action group website for further information.

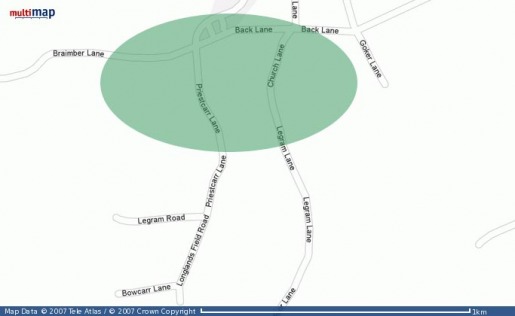

This find, although a single object, when compared to Map 1 showing the location of springs in the area around Marton Cum Grafton, begins to draw us to our first conclusion: that the early settlements in the area around Marton Cum Grafton were not where the current village lies, but in actual fact, in the area marked by the green oval on the map above. This is significant, as we shall see, when we discuss later periods of the village history.

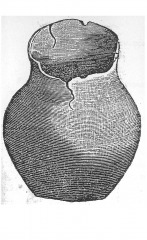

Another significant find was the Tumulus at Deuil- Cross, which was on the east side of the York/Boroughbridge Rd. (Dere Street) by the turn off to Great Ouseburn and Upper Dunsforth, similar to the one below:

Hargrove has documented the findings as follows: “Deuil-Cross ; whose elevation was about 18 feet, and circumference, at the base 370 feet (this is large by tumuli standards). It was broken into, some time since, to supply materials for the repair of the turnpike-road (the tumulus, by this means, hath quite disappeared; and, the place is now a sand-pit) leading from Aldbrough to York.

The soil consisted, first, of black earth, and under that, a red sandy gravel; human bones, entire, and urns, of various sizes, containing burnt bones and ashes.

The urns are composed of blue clay and sand, generally very coarse; some ornamented, and others quite plain. The annexed print is a representation of one of them, dug up here, in the year 1756; now in the possession of Humphrey Senhouse, esq., of Nether-hall, near Cockermouth. It was nine inches in height, and 32 in circumference”.